by R. Nandini and Sanjay Sane

In popular folklore the appearance of certain birds is considered to herald the approaching rains. But there are other, less conspicuous, organisms whose arrival often goes unnoticed. Migratory insects of several species arrive in the thousands, either alone or in swarms, staggered across the days preceding the arrival of the rains.

In a recent paper that generated headlines worldwide, Globe Skimmer dragonflies Pantala flavescens (also called Wandering Gliders) were discovered to have the longest insect migration route recorded so far – a roundtrip flight between India and Africa with stopovers in the Maldives and the Seychelle islands.

In a recent paper that generated headlines worldwide, Globe Skimmer dragonflies Pantala flavescens (also called Wandering Gliders) were discovered to have the longest insect migration route recorded so far – a roundtrip flight between India and Africa with stopovers in the Maldives and the Seychelle islands.

Charles Anderson, reporting his findings in the Journal of Tropical Ecology <1>, recorded the arrival and departure of dragonflies in southern India, Maldives and West Africa over a period of fourteen years, with Malé, Maldives being the focal site. Dragonfly occurrence (particularly P. flavescens) in Malé began in October, peaking between November and December, coinciding with the east-bound high-altitude winds (~ 1000 m asl) of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ <2>).

Putting together dates of arrival across the study sites as well as the duration of residency of dragonflies at Malé, he reconstructs a steady north-south movement of dragonflies from southern India through the Maldives across 500-1000 km. A second wave of dragonflies was recorded in Malé between April and June, coinciding with occurrence of the Somali Jet, a band of fast low-lying southwesterly winds over the Arabian Sea blowing from Africa to India.

Putting together dates of arrival across the study sites as well as the duration of residency of dragonflies at Malé, he reconstructs a steady north-south movement of dragonflies from southern India through the Maldives across 500-1000 km. A second wave of dragonflies was recorded in Malé between April and June, coinciding with occurrence of the Somali Jet, a band of fast low-lying southwesterly winds over the Arabian Sea blowing from Africa to India.

While this study was focused on dragonflies, Anderson also reports some information on birds, and found that the pattern of bird arrival in the Maldives mirrored that of the dragonflies, peaking between November and December. Among the bird species he reports as crossing the Western Indian Ocean are the Pied Cuckoo, Lesser Cuckoo, Eurasian Cuckoo and the Amur Falcon.

Collating available information on the migration of birds like the Amur Falcon, wind patterns like the ITCZ and Somali Jet, and records of occurrence of certain species of dragonflies at specific times of the year in the Maldives and India, Anderson hypothesizes that dragonflies, like some species of birds, possibly migrate in a loop from India over the Maldives and Seychelles to east Africa (Tanzania or Kenya) and then back again to India. The ITCZ is known to travel across the African continent, bringing rains to different parts of Africa over the year <3>, and insect, including dragonflies, are reported to migrate with these winds. Anderson suggests that, once in Africa, Globe Skimmers probably move southwards and then loop back north to equatorial east Africa before leaving the continent on the return migration to India.

In all, this incredible circuit would cover a total distance of 14,000-18,000 km, with 3,500 km over the open ocean, and would span possibly four generations of dragonflies.

How could insects only a few inches long undertake journeys that span their own body lengths several million times over? On the face of it, this implies deterministic and purposeful flying, as well as knowledge of which winds to harness to get to a destination. Anderson proposes instead that dragonflies need only rise upwards, encounter a passing wind and then largely soar or glide along this wind till they reach land. If this simple explanation is indeed the way in which dragonflies cover these enormous distances, how will such behaviour be affected by phenomena like global warming, which is known to alter the intensity and speeds of winds like the Somali Jet <4> and the ITCZ?

Dragonflies are reputed to be powerful fliers, and several species migrate long distances <5>. The Globe Skimmer is considered to be the most widespread dragonfly, occurring between the 40th parallels of latitude worldwide, and it is common across India <6>. Several populations of this species are known to migrate, and there are recorded migrations of Globe Skimmers from South America to Easter Island (possibly 3,600 km or more), to New Zealand (2,000 km), across the Chinese Bohai sea (nocturnal migrations) and over the Hindu Kush mountains (at altitudes of 6,500m asl). Within the Indian subcontinent, the Globe Skimmer arrives in Tamil Nadu after the North-East Monsoon, while in the western regions it arrives with the South-West monsoon, implying that there might be more than one migratory circuit even within this region.

While dragonflies and insects remain challenging to track over long distances, a number of studies have used arrival date information, mark-recapture techniques, and even radio-telemetry <7> to determine their migratory patterns. But, given the epic scale of the migration uncovered by Anderson, perhaps it would make sense to simultaneously examine both more visible taxa like birds and more populous taxa like insects. Doing so might provide a more comprehensive account of migratory patterns, mechanisms, and the evolutionary reasons for these spectacular journeys.

References

1. Anderson, R.C. 2009. Do dragonflies migrate across the western Indian Ocean? Journal of Tropical Ecology 25(4): 347-348. Download pdf.

2. The ITCZ is a weather system around the equator where the North-East and South-West trade winds converge. More information.

3. The ITZC in Africa. http://people.cas.sc.edu/carbone/modules/mods4car/africa-itcz/index.html

4. Meijing, L., Ke, F. and Huijun, W. 2008. Somali Jet Changes under the Global Warming. Acta Meterologica Sinica. 22 (4): 502-510. Download pdf.

5. Corbet, P. S. 1999. Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

6. Subramanian, K.A. 2005. Dragonflies and damselflies of peninsular India. A field guide. Edition 1.0. E-book of Project Lifescape, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science and Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore, India. 118 pages. Copyright K.A.Subramanian, 2005. Download pdf.

7. Wikelski, M., Moskowitz, D., Adelman, J.A., Cochran, J., Wilcove, D.S. and May. M.L. 2006. Simple rules guide dragonfly migration. Biology Letters, 2: 325-329. (Wikelski and colleagues radio-tagged 14 dragonflies in North America and followed them for 12 days with Cessna planes and ground teams.) Download pdf.

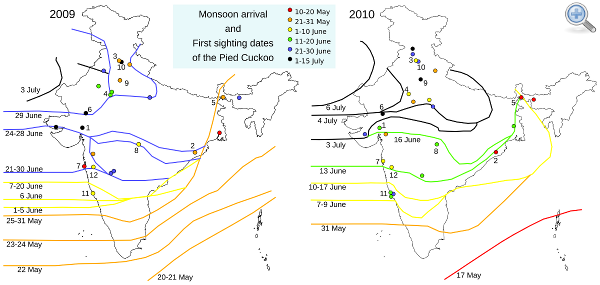

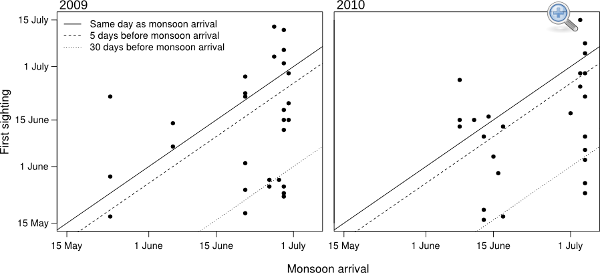

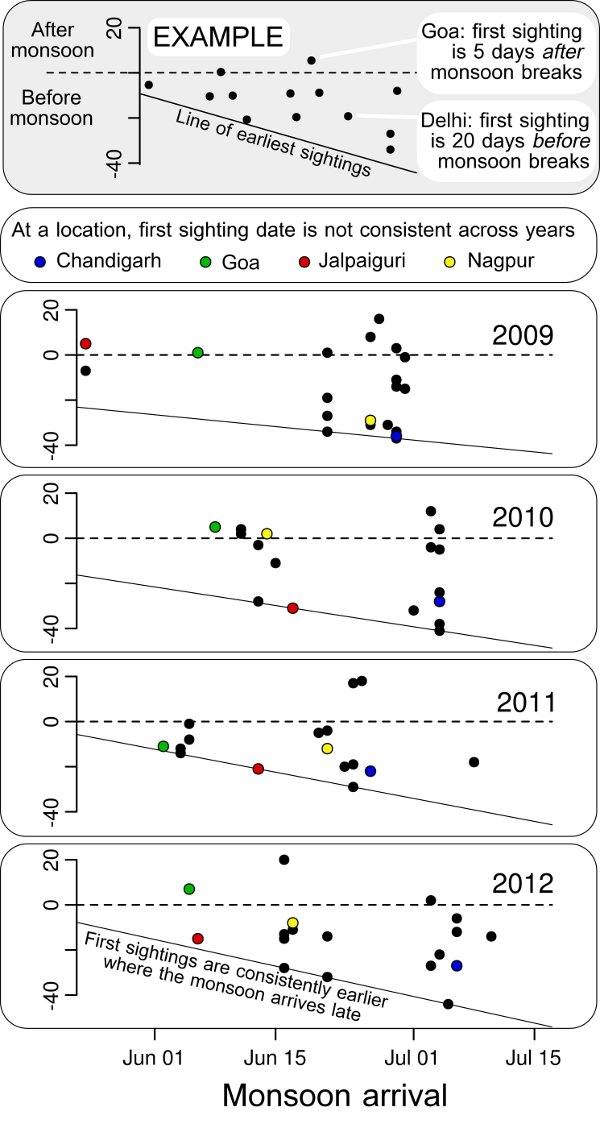

To illustrate the general pattern of migration of this species, we have put together this animated map, which shows the progression of Pied Cuckoo migration across the country in advance of the monsoon.

To illustrate the general pattern of migration of this species, we have put together this animated map, which shows the progression of Pied Cuckoo migration across the country in advance of the monsoon.