By Mousumi Ghosh (with inputs from Umesh Srinivasan)

Tips for Identification

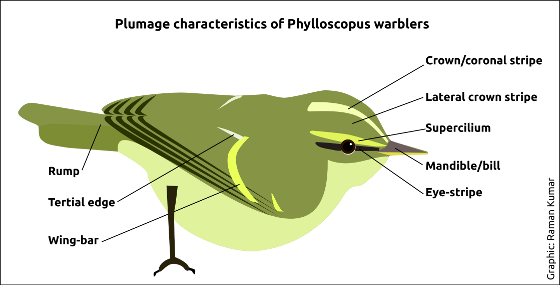

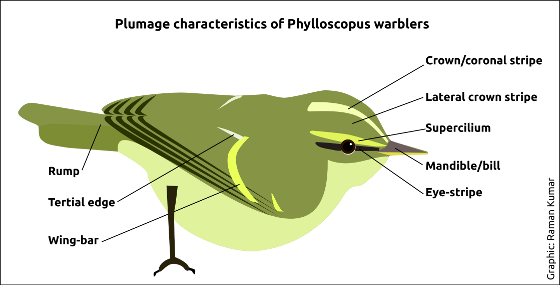

If you’re keen to start leaf warbler watching, you just need an ear for it! You can start with the commonly encountered leaf warbler species in our backyard like Hume’s Warbler (in North India) and Greenish Warbler (in South India) and fortunately, both are extremely vocal. Anytime I want to hear a Hume’s Warbler in winter here in Dehradun, I just have to strain my ears a bit and sure enough I can hear one (yes, it’s that common during winter in North India). Both are territorial in winter and call incessantly guarding their precious trees from the canopy. So, let’s get acquainted with some of the commoner species which visit us in the plains in winter (Here is an illustration to help you with some of the terms commonly used while describing warblers):

Hume’s Warbler (Phylloscopus humei): One of the commonest leaf warblers, it has an overall dull colour with greenish upperparts and off-white underparts. Other features include a long supercilium, weak/absent crown-stripe, prominently pale tertial edges, no white margins to the tail, one prominent pale wing bar (just a faint vestige of the second wing bar may be visible). The darker legs and lower mandibles are diagnostic. Hume’s is among the smaller of leaf warblers; it breeds near the tree-line and is partial to birch forests in the summer. In the winter it is one of the commonest species found all over the plains of North India. It’s solitary in winter and calls incessantly from the crowns of trees. Call: A repeated, disyllabic ringing tiss-yip, buzzy wheezing tzzzeeeeeu, often given interspersed with calls.

Hume’s Warbler (Phylloscopus humei): One of the commonest leaf warblers, it has an overall dull colour with greenish upperparts and off-white underparts. Other features include a long supercilium, weak/absent crown-stripe, prominently pale tertial edges, no white margins to the tail, one prominent pale wing bar (just a faint vestige of the second wing bar may be visible). The darker legs and lower mandibles are diagnostic. Hume’s is among the smaller of leaf warblers; it breeds near the tree-line and is partial to birch forests in the summer. In the winter it is one of the commonest species found all over the plains of North India. It’s solitary in winter and calls incessantly from the crowns of trees. Call: A repeated, disyllabic ringing tiss-yip, buzzy wheezing tzzzeeeeeu, often given interspersed with calls.

Greenish Warbler (Phylloscopus trochiloides): A common winter migrant in peninsular India, it is one of the larger leaf warblers. It has greyish-green upper parts and off-white underparts. Absence of coronal stripe, yellowish-white supercilium and a single wing bar are other features which help distinguish this species.

Greenish Warbler (Phylloscopus trochiloides): A common winter migrant in peninsular India, it is one of the larger leaf warblers. It has greyish-green upper parts and off-white underparts. Absence of coronal stripe, yellowish-white supercilium and a single wing bar are other features which help distinguish this species.

During the breeding season, Greenish Warbler occurs close to the tree-line in mixed-conifer forests and rhododendrons. In winter, it is territorial and partial to the canopy, from the top of which it calls incessantly to defend its precious territory. Call: a disyllabic tisswit or chiswee.

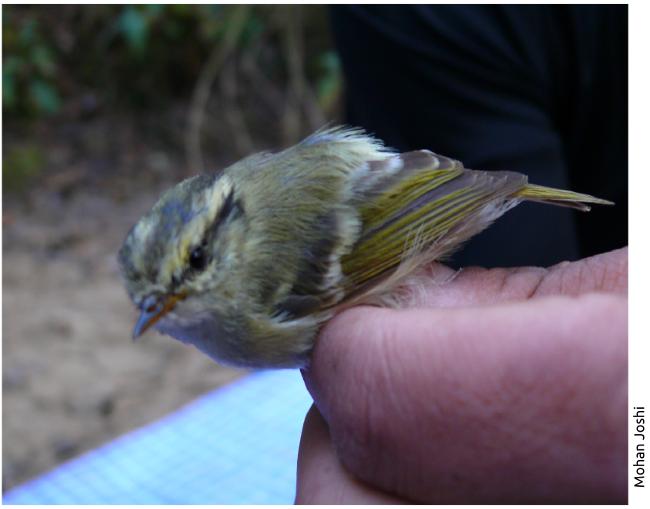

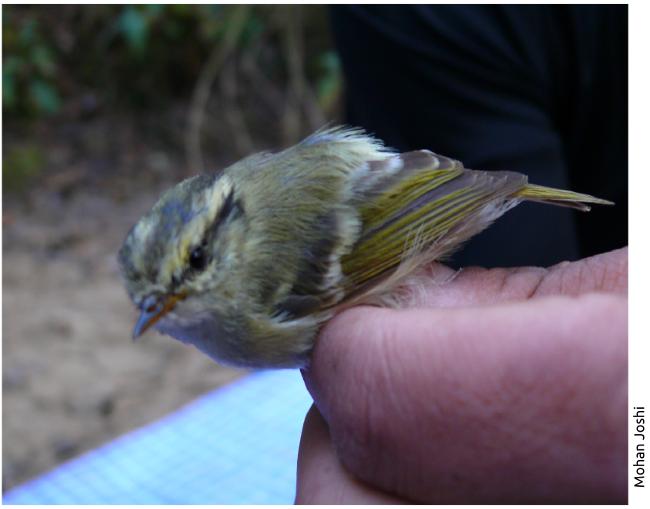

Lemon-rumped Warbler (Phylloscopus chloronotus): This tiny little leaf warbler gets its name from its pale yellowish rump which is frequently exposed as it hovers at the edge of leaves to pick arthropod prey. It’s a rather active bird with olive  green upperparts, whitish underparts, dark bill and pale legs. The head is rather distinctive with a prominent pale yellow crown stripe, a broad yellowish supercilium and a very dark eye-stripe which broadens behind the eye and hooks under the ear coverts. Typically two yellowish wing bars are visible, the lower one being larger and more prominent. This species is an altitudinal migrant, spending the summer in the mixed coniferous, oak and rhododendron forests and retreating to the foothills in winter where it joins mixed-species flocks to forage mostly in the mid-canopy and undergrowth. More than two may be part of the same flock, daintily hovering around the vegetation and is an absolute treat to watch! Call: A high-pitched tsip or uist.

green upperparts, whitish underparts, dark bill and pale legs. The head is rather distinctive with a prominent pale yellow crown stripe, a broad yellowish supercilium and a very dark eye-stripe which broadens behind the eye and hooks under the ear coverts. Typically two yellowish wing bars are visible, the lower one being larger and more prominent. This species is an altitudinal migrant, spending the summer in the mixed coniferous, oak and rhododendron forests and retreating to the foothills in winter where it joins mixed-species flocks to forage mostly in the mid-canopy and undergrowth. More than two may be part of the same flock, daintily hovering around the vegetation and is an absolute treat to watch! Call: A high-pitched tsip or uist.

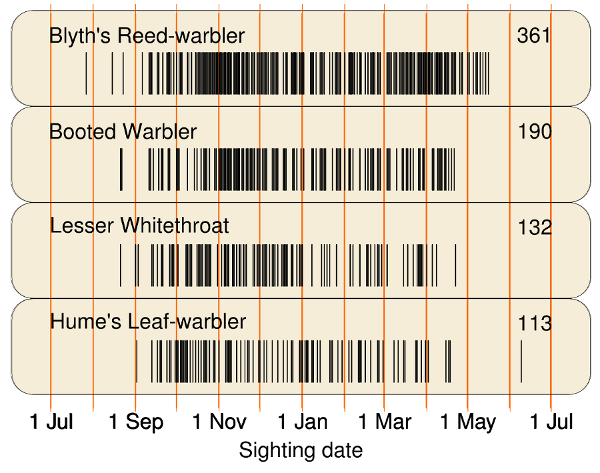

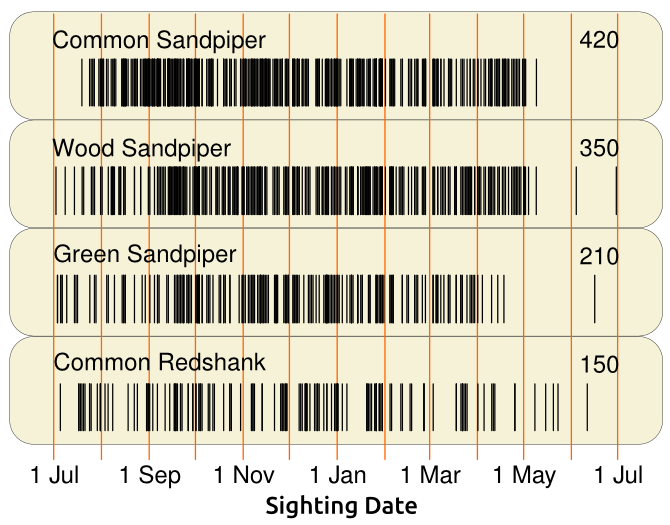

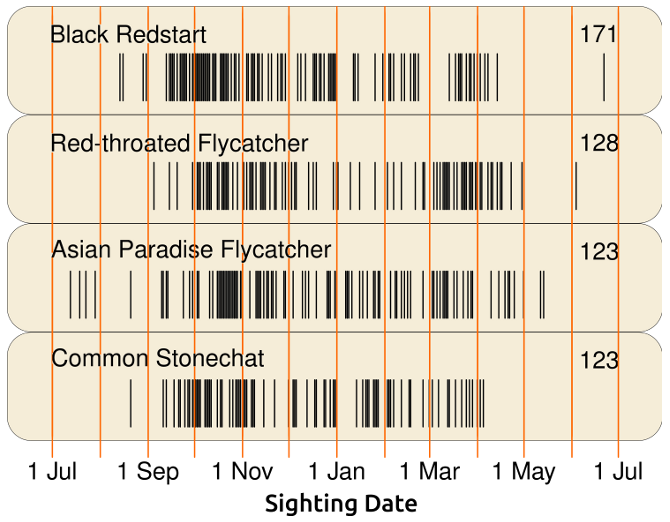

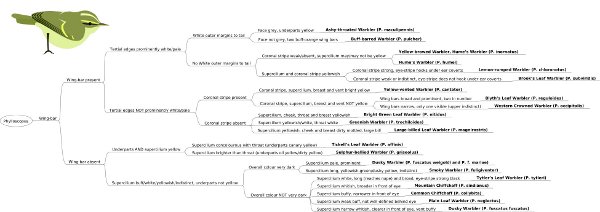

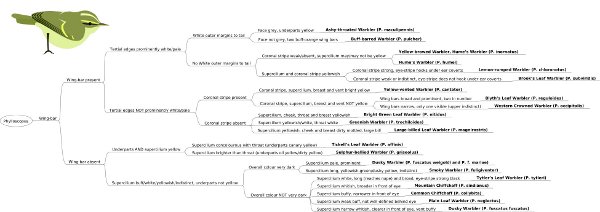

Apart from the above there are a number of other species of Phylloscopus warbler that can be observed in the Indian subcontinent. Most of these species migrate over long distances to winter in the Indian plains and peninsular India, some show an altitudinal migration, and a couple of them are resident throughout the year. Here is a very handy key for their visual identification compiled by Umesh Srinivasan.

This concludes our three-part series on Phylloscopus warblers. We hope that these articles helped you in identifying the main species in this difficult group and also provided interesting information about the ecology of leaf warblers. We’d like to know if you liked this series and if you’d like us to run more such articles in the future on the MigrantWatch blog. Please do send in your comments and feedback at mw@migrantwatch.in.

You can read Part I and Part II in this series of articles on leaf warblers.